To feel for Art, is to Sense the Yearning and Mystery of the Human Heart.

Recently, I’ve noticed lots of articles and images popping up on social media, here and there, showing examples of “art” created by AI technology.

MidJourney, DALLE.E, are two machine names that lead you to a website where you can type a couple of words into the search box, push a button, and it will generate a work of art based on those words.

I presume that we are supposed to sit in wonder, and enjoy the results of an effortlessly machine generated work of art.

I am sure that there are some who might even imagine that it’s their own work — somehow, the AI generated image is a reflection of their own ideas. mmmm?

I thought I’d have a go at it.

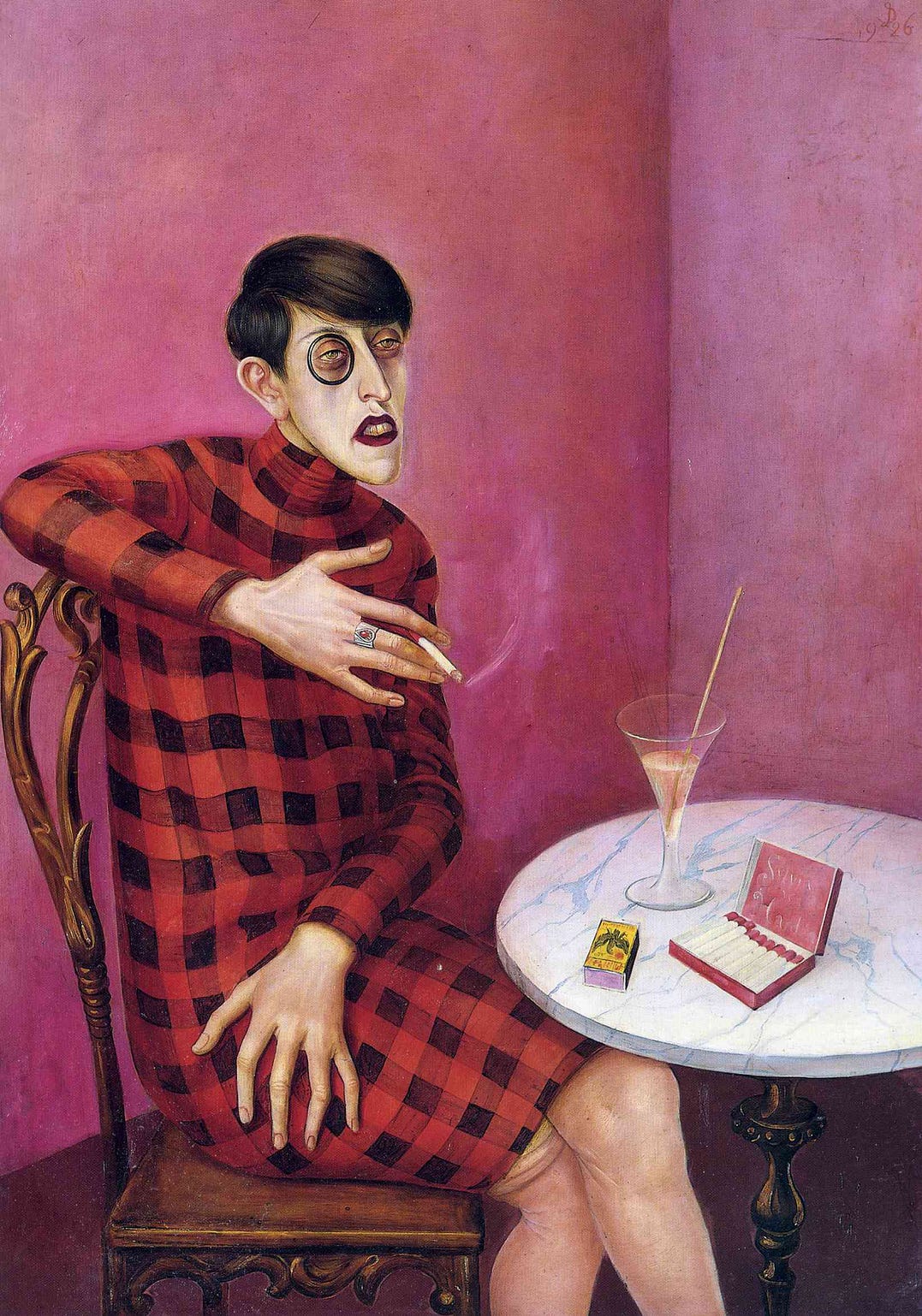

My first attempt, the name Otto Dix came to mind. A favourite painter of mine, German art of the 1920s onwards till the 1930s, until he was forced into exile by the rising of the Third Reich.

Otto Dix was preoccupied with society under pressure. Poverty, death, and the under dogs of society gripped his thoughts.

His works of First World war soldiers in the trenches, amidst a burnt and scarred landscape, evokes thoughts of hell.

His other works of women in a brothel, waiting for new custom, they are worn and tired. Exhausted faces filled with a lack of care or regard for their circumstances.

And his post First World War paintings of ex-soldiers, missing legs, wooden props, disfigured faces after fighting for their country. Now left to sell matches on the streets.

The paintings of Otto Dix are the response of a man observing his environment. His lack of power to change things led to the need to at least paint it, and keep it, so at least we can be second witness to what he saw.

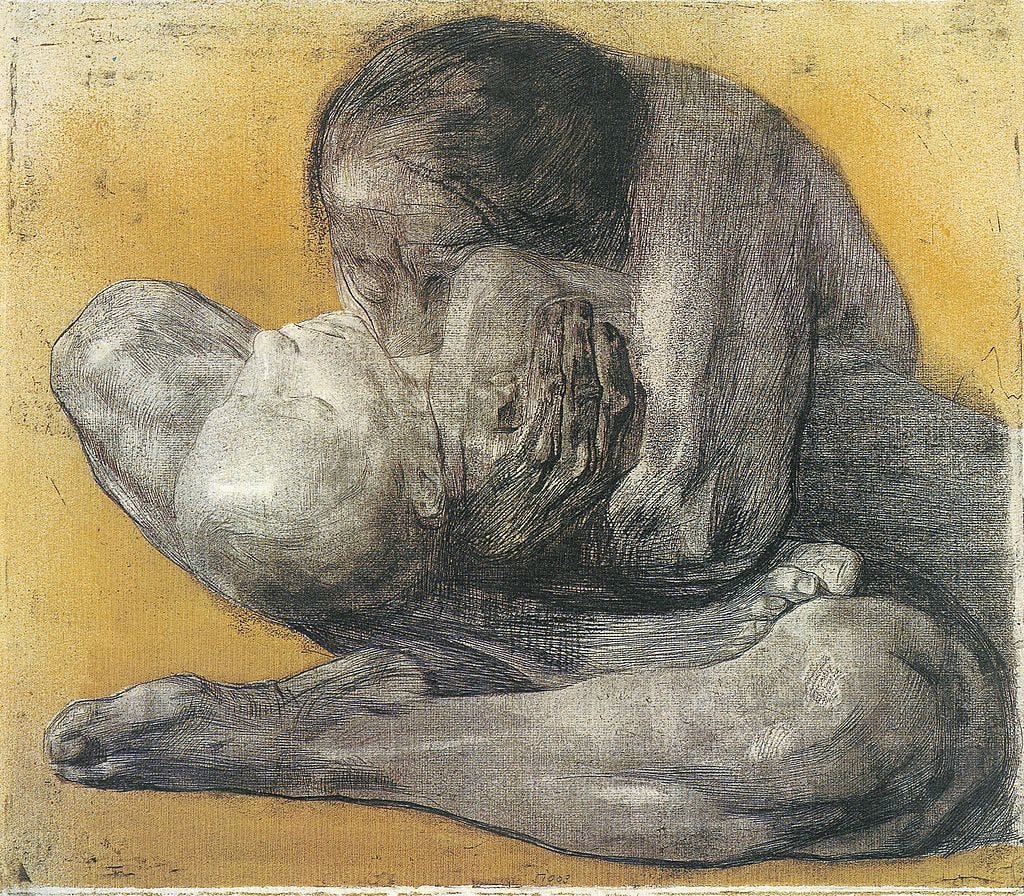

I always see a strong connection between Otto Dix and Käthe Kollwitz. She sketched the poverty, and the dangers that mothers and young women were left to endure on the streets of Berlin.

Käthe Kollwitz’ work shows us the inhumanity of that time. Otto Dix shows us how a society of bankers and industrialist could dance around their coffers, filled with cash, while others starved on the streets.

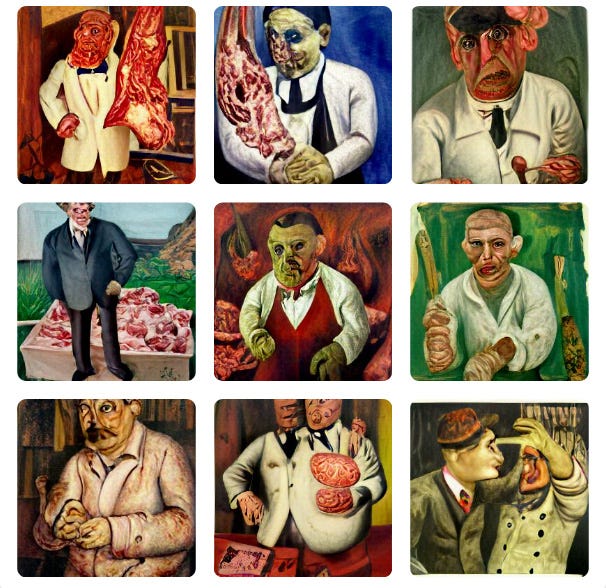

Below is a colour plate generated as images related to the words, Otto Dix, Butcher, Painter.

I have no idea whether they are a mixture of AI and oil sketches by the artist, or only generated AI images. They are rough and appear to be attempts at depicting an idea.

The use of expressionism, caricature, and humour, digs deeply into the psyche.

It creates a style known as New Objectivity it was plenty enough to stop me in my tracks, long ago in a Berlin art gallery, it made me think deeply about the artist.

About how he came to paint these ideas, and why. He must’ve felt close to his subjects.

At first, I thought Otto Dix must be English — I saw the humour in his paintings. But my German companion assured me, that one, he was German, and two, Germans always have had a sense of humour. It’s just that it’s a German sense of humour, not an English one.

The connection here is that I can feel for Otto Dix and his work. I relate because I’m a human being, and he was too. We both lived in different times, but both experienced life, and all its problems. I can trust him.

He tells me of his unique problems of life, and what he saw, through his paintings. It makes me glad that I live in a relatively peaceful time.

I often wonder how people who lived in Berlin during the war managed to get through it. I don’t know. I know that my parents’ generation, English and Irish, who suffered the blitz in London, never wanted to speak of it again.

If we asked questions, they would look on the bright side, and say, “We’re all glad that we got through. We can now enjoy life in peace.” That was about all they could say of an experience that was beyond words.

My Grandmother went through two World Wars. Her husband fought in Flanders, was wounded, captured and spent a year as a P.O.W., both the Germans and the English prisoners in the prison camp decided that for them the war was over — far away in the Fields of Flanders. So they went back to treating each other with respect. My Grandfather and a German prison doctor kept up a correspondence after the war. They became friends by writing postcards to each other for a short while.

In one postcard, written by the doctor, he tells my grandfather, in German, that, “The Heinzelmännchen are still busy at the front, John.” and he included a small thumbnail pencil sketch of the Heinzelmännchen rolling up the barbed wire across the Western Front. German humour between two men forced to become enemies. Their friendship and the humour they shared opened a better way to relate to each other.

Heinzelmännchen are mythical Gnomes who do all the work while we sleep at night.

I can’t imagine that a computer generated image could ever evoke such emotion in a human being as do the paintings and writing of real people who experience the common problems of human existence.

A postcard from a perceived enemy, now friend, holds a deeper meaning than the wow! factor that we constantly have to put up with in this computer age.

Currently, AI can generate ideas related to human existence. It can pump out an image, or write an essay about any whim and fancy that we ask of it. But all of its output is information gathered from the internet.

It stands aloft, looks down onto all the information that we type into the machines, and gathers it into preset ideas of what harvested information should look like. Orderly ideas to impress us with. Images that are like these ones, or those ones.

A compilation of thoughts and ideas, fragments that seem to fit the topic, artificial intelligence can amaze us with how quickly it does this, and how similar the ideas are to what we already know.

It’s accurate in that it knows what fits together, But it doesn’t care for us, nor does it help us be better humans. It probably won’t use human desire and will to forge friendships between enemies. It would rather offer a solution on how to destroy your enemy, and that you should always perceive them as such.

A postcard from the Front is more powerful than an AI generated similarity. A painting that evokes terrible memories of poverty will move a human to action more quickly than a computer generated solution to a problem.

Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz and many more who painted and wrote books about life are the very basis upon which AI intelligence must rely.

How long will it be before AI starts to repeat itself, reveal its weakness and start making things up for us?

It can only gather information, collate it into orderly sets of ideas, then present it in a form that we recognise as an image or an article written in the style of a great writer.

It can do this with astonishing speed and agility, but never can it generate any of the mystery and yearning of a human heart. I don’t trust it, nor will I spend my time pondering computer generated images that come from gleanings and fragments of human existence.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.